The Exigence

Saudi Arabia is one of the leading countries that publicly and systematically discriminates against women. The case of banning women from driving in Saudi Arabia is indeed an illustrative example. However, the use of social media to mobilize women concerning their rights was remarkable in generating support and influence. However, the novelty of this topic, the language barrier, and the conservative culture might be leading to a paucity of academic research pertaining to the study of social media activism to affect women’s rights in Saudi Arabia especially concerning rhetorical circulation. The significance of the circulation of discourse relies on the fact that it is responsible for both creating a public and affecting the conditions to achieve social and political objectives. Nevertheless, the circulation of discourse in this study will be identified as online activism and online influence. Both online activism and online influence (the circulation of discourse) on social media might be affected by other factors, in this case the results will be analyzed accordingly.

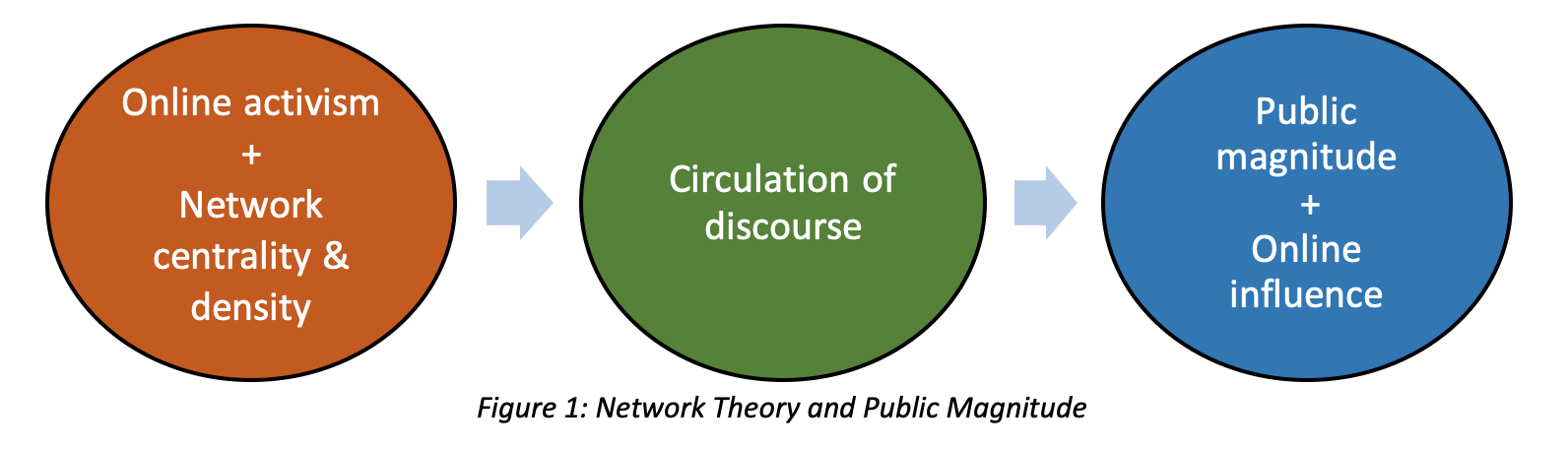

But, how can we measure rhetorical circulation and overall results? To answer this question, I will test and apply network theories, namely, network centrality and density (explained in the next section) on some of the activists’ networks/interactions on Twitter to understand how the magnitude of a public or online influence to achieve social and political objectives (activism results) are contingent on network centrality and density and activism intensity. Scholars have argued that high network centrality and density with high online activism can bring better awareness and greater transmission in the network, hence effecting online influence. In this case, if high online activism combined with high network centrality and density yield high online influence, then the rhetorical circulation (online activism and online influence) is contingent on network centrality and density. This thinking shows how essential network structures, namely, network centrality and density, in affecting rhetorical circulation and the magnitude of a public.

Overall, this study provides a prototype methodology which could be considered in future research to examine/study the effect of network centrality and density on rhetorical circulation of different activism cases on Twitter. That is, network theory can provide a way to understand how similar or different cultures participate in activism, for example, compare and contrast network structures and their effect on rhetorical circulation of culturally similar/different activism cases. Network theory not only can be used to examine, measure, and analyze a public on social media, but also it allows us to understand how we can achieve better awareness and greater information transmission and diffusion within online social networks in cases of social or political activism.

Before I conduct the study, I will provide a brief background of the struggle of women in Saudi Arabia in claiming their right to drive and in mobility in general. After I conduct the study, I will address some of the limitations that I have encountered, followed by recommendations for further research. In the next section, I will provide more in-depth explanations of the theories.

Network and Rhetorical Theories

In network theory, David Knoke and Song Yang (2008) in “Social Network Analysis” elaborate on the positive correlation between direct connections between nodes (centrality or betweenness) combined with intensive interactions (activism) and “better information, greater awareness, and higher susceptibility to influencing or being influenced by others” (p. 5). Centrality or betweenness refers to the degree of which nodes stands between each other (Knoke and Yang, 2008). As for density, Charles Kadushin (2012) in “Understanding Social Networks: Theories, Concepts, and Findings” describes density as the heart of community and responsible for transmission. He states, “the greater the density, the more likely is a network to be considered a cohesive community, a source of social support, and an effective transmitter” (p. 29). Therefore, intensively active online activists whose networks are highly central and dense are more likely to diffuse better information and greater awareness and effect online influence (Kadushin, 2012, p. 32 and Knoke and Yang, 2008, p. 5).

From a rhetorical perspective, Michael Warner (2002) in “Publics and Counterpublics” argues that rhetorical circulation creates publics, saying: “The existence of a public is contingent on its members’ activity … A public is the social space created by the reflexive circulation of discourse” (pp. 61-2). Further, Brandon Inabinet (2012) in “Democratic Circulation: Jacksonian Lithographs in U.S. Public Discourse” shows how circulation of images is germane to the ways in which social change can be achieved. Nevertheless, Sean O’Rourke (2012) in “Circulation and Noncirculation of Photographic Texts in the Civil Rights Movement: A Case Study of the Rhetoric of Control” illustrates how strategic circulation can buttress political purposes. Based on the literature above, we can conclude that high online activism intensity, combined with high network centrality and density, yield effective transmission and greater awareness, hence high online influence. The circulation of discourse (online activism and online influence) is responsible for creating a public and affecting ways to achieve social and political objectives. Therefore, I argue that online activism combined with network centrality and density can affect the circulation of discourse, the magnitude of a public, and the activism results (online influence) as illustrated in Figure 1.

,p>

,p>

Brief History of Women Driving Activism

The quest of Saudi women to effect change and achieve parity with their male counterparts in the right to drive has a long history that started on November 6, 1990 when a group of women defied the ban and drove in public in the capital city of Riyadh to draw the government and the public’s attention to their right to drive. These forty-seven women who were physicians, professors, school teachers, housewives, and students were detained, fired from their jobs or expelled from schools, and banned from traveling outside of the country for an entire year (al-Māniʿ and āl-Shaykh, 2013, pp. 55-61). Furthermore, the Saudi religious establishment initiated a counter campaign that sought to delegitimize the women by humiliating, defaming, and spreading lies throughout the kingdom by distributing publications to public institutions like schools and mosques. These publications included their names, ages, their male guardians’ names, their ideologies (e.g., communist or secular) and their citizenship status (Some of them were of Saudi-American dual citizenship.). Also, in those publications, a letter was included and addressed to Muslim women in the kingdom warning them from the “harlots and agents of the West” targeting the Islamic fabric of the Saudi society (al-Māniʿ and āl-Shaykh, 2013, pp. 69-74).

Nevertheless, nearly two decades later, on Saudi Arabia’s National Day on September 23, 2007, more than 1,100 women and men petitioned King Abdullah (r. 2005-2015) to lift the ban on women driving (Kéchichian, 2013, p. 179). Among the petitioners was Wajeha Al-Huwaider who attracted international media attention on International Women’s Day in 2008 when she protested the ban on women driving in Saudi Arabia by driving in public, filming herself, and posting it on YouTube (Human Rights Watch, 2013, para. 13). Then, on May 21, 2011, inspired by the Arab spring, Manal Al-Sharif drove her car while being filmed by Al-Huwaider and uploaded the video on YouTube. This video went viral and led to her arrest. She was held in custody for ten days, “a period of time that literally mobilized Saudi society” (Kéchichian, 2013, p. 180). After her release and over the course of several weeks, 30 to 40 women across the country took to the wheel; seven of them were placed in custody for participating in the "Women2Drive" campaign in June 2011 (Kéchichian, 2013, p. 181). Then, on October 26, 2013, another campaign was initiated to defy the ban; the campaign received significant attention locally and internationally. The signatures collected on that day exceeded 15,000 before the Saudi officials blocked the website as reported by USA Today (Stanglin, 2013, para. 11).

Some activists received phone calls from employees of the Interior Ministry telling them not to drive on that day. Despite the warning and the heavy police presence in most of the major cities in Saudi Arabia, more than 60 women drove their cars. As The Guardian reported, “A Saudi professor and campaigner, Aziza Youssef, said the activists have received 13 videos and another 50 phone messages from women showing or claiming they had driven, the Associated Press reported” (“Dozens of Saudi Arabian Women,” 2013, para. 3). Moreover, on December 1, 2014, another incident of defying the ban on women driving was initiated by Loujain Al-Hathloul who was arrested and detained along with her friend Maysaa Al-Amoudi for driving and crossing the border of Saudi Arabia from the United Arab Emirates while both holding valid Emirati driver’s licenses. Al-Hathloul documented her driving and posted it on Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter generating serious attention from people and from the media (Mackey, 2015, para. 1-3). The New York Times reported that Al-Hathloul and Al-Amoudi were detained for 73 days (Mackey, 2015, para. 1), and The Atlantic published an article regarding this specific incident entitled “Saudi Women Drivers Sent to Terrorism Court” (McDuffee, 2014, para. 1).

The Rhetoric of Mobility

The first attempt to defy the ban on women driving was during the Gulf War in 1990. When Iraq invaded Kuwait, it was one of the few times when the society panicked and feared for their future. This drove many of the expatriates to leave the country, and among them were the drivers for Saudi families. Attempting to prevent this, some families offered their drivers three times their normal salary to keep them from leaving. This instability brought on by the war led some women to think about their families’ security and safety, and therefore, they wanted to lift the ban on women driving in case of emergencies (al-Māniʿ and āl-Shaykh 2013, 24-26).

Although the Gulf War provided a suitable context for women to question the ban on driving, women’s need for driving remains. Women need transportation to run their errands and to commute to their jobs. There is a huge demand for women to occupy positions as teachers, professors, and physicians. In Saudi Arabia, public schools and university are segregated by gender (Al-Saif, 2013). Therefore, there is a demand for both genders to teach at the different gender-based schools. Furthermore, female physicians are also in high demand since some men do not allow their wives, daughters, or sisters to consult with male doctors (For an unfortunate example of this see the article published by The Daily Mail entitled “Saudi father shoots doctor shortly after he delivered his wife's baby because he didn't want a man to see his spouse naked” (Wyke, 2016).).

In addition, women need safe and reliable modes of transportation to commute to and from work, yet Saudi Arabia has limited, inferior, and unsafe public transportation. Echoing that, Arab News stated in an article, “Yet the low quality of public transport in the Kingdom remains a source of dissatisfaction for low- and middle-class citizens” (Fayyaz, 2013). Many cities have witnessed female teachers perish in car accidents either going to or returning from their job. For instance, the Saudi Gazette stated that a “recent study indicated that around 150 female teachers died in accidents last year alone [2014]. The study noted 56 percent of vehicles used for transporting teachers are not fit to travel on highways while a further 22 percent have worn out tires, Al-Riyadh Daily reported” (“Study shows accidents involving…”, 2015).

Moreover, studies have shown that the number of fatalities in Saudi Arabia caused by road accidents is among the highest in the world, with a steady increasing trend in road traffic fatalities due to reckless driving, according to World Health Organization. Arab News reported that “authorities disclosed that at least one traffic accident occurs in the Kingdom every minute. Saudi Arabia witnesses up to 7,000 deaths annually, and over 39,000 injuries per year” (“Traffic accidents occur…”, 2015). Further, there is a growing number of illegal driving by minors which contributed to more accidents and unsafe transportation: “About 70 percent of the accidents that occur in the Kingdom are of minor sort” (“Traffic accidents occur…”, 2015).

Nevertheless, harassment and sexual assaults are the chief concern for women in Saudi Arabia when they are riding with public or private drivers. Whether the drivers are native or expatriates, harassment and sexual assaults are on the rise. For example, Al Bawaba reported that a Saudi driver kidnapped a girl because he wanted to prevent her from dating a guy in Riyadh (“Saudi driver kidnaps …”, 2018). Also, the Saudi Gazette and Arab News have reported on several sexual harassment cases that women in Saudi Arabia have faced (Al-Fawzan, 2014; “Private drivers and sexual …”, 2017; Khan, 2014).

As illustrated, mobilization on social media and the need for safe and reliable transportation have helped women in Saudi Arabia to create a momentum that contributed to online influence and the growing number of activists and supporters of both genders, and hence to finally announcing women as equal citizens to their male counterparts in the right to drive on September 26, 2017 (Hubbard, 2017). To this end, it seems necessary to examine some of the activists’ network structures on Twitter to understand how their online activism and network centrality and density affect the magnitude of a public and effect online influence.

Method

To conduct the study and show how online activism and network centrality and density affect the circulation of discourse to effect online influence, I consider the following:

1- The activists

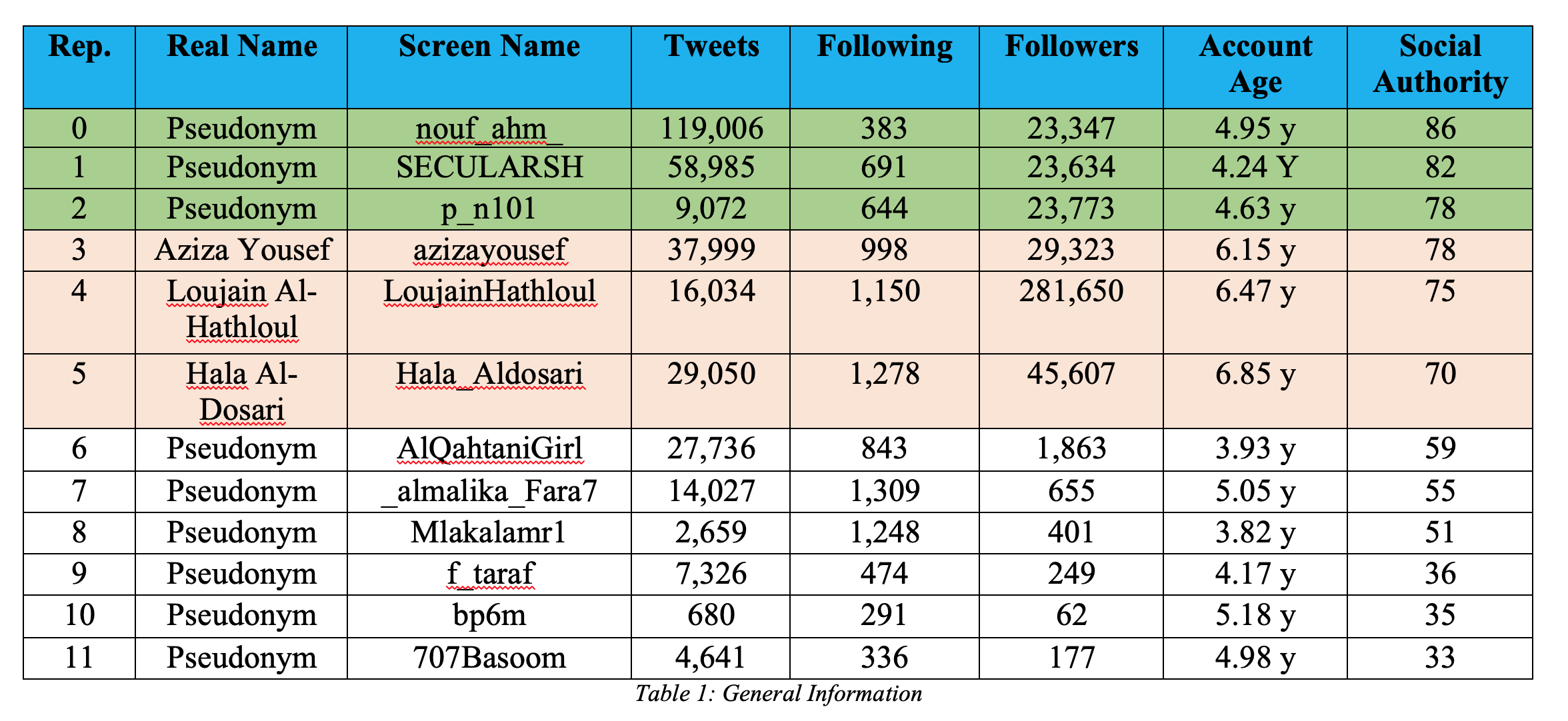

a. I have selected twelve female Twitter activists. Three of them are Aziza Yousef, Loujain Al-Hathloul, and Hala Al-Dosari who are well-known in Saudi Arabia for their daring and risky online and offline activism related to women’s rights (Yousef and Al-Hathloul are detained in Saudi prisons for their women’s rights activism since May 2018, Fahim, 2018. There is not telling when they will be released as now January 2019). In addition, they have the most central and dense networks comparing to other activists in this study. The other nine activists who are using pseudonyms are among Yousef, Al-Dosari, and Al-Hathloul’s mutual followers. The rationale behind choosing them is to calculate the density of each activist’s network. The density of network is calculated by dividing the number of each activist’s followers by the sum of all activists’ followers (potential followers). This will be explained later.

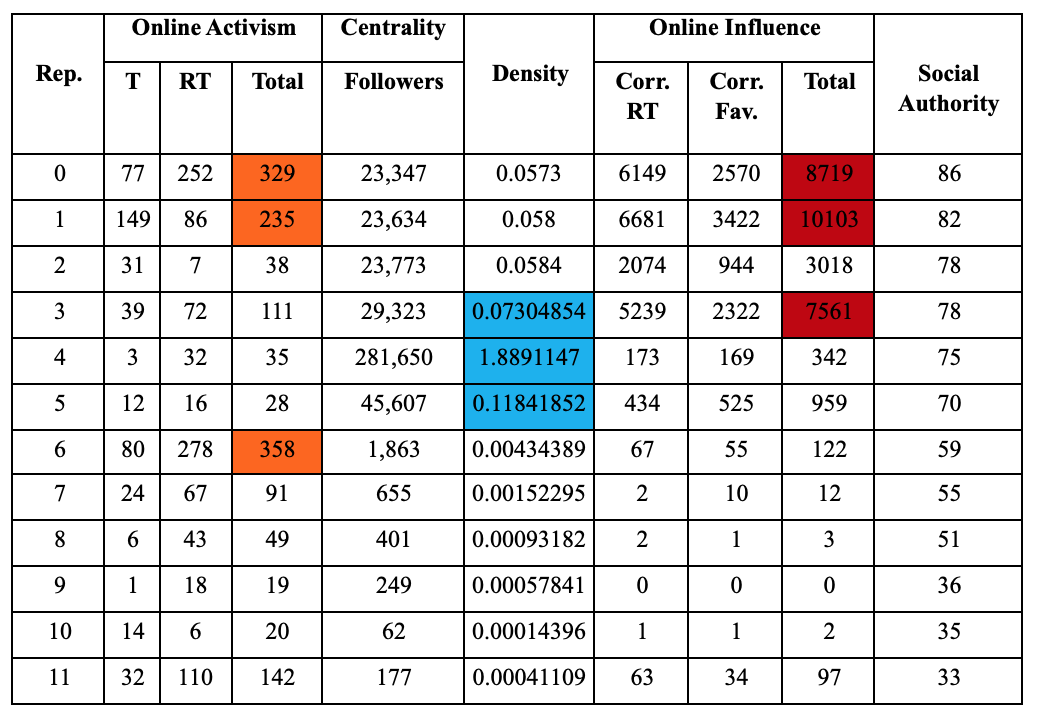

b. Another measure to choose the activists was “social authority” which was provided by Followerwonk application. This feature is a 1 to 100-point scale that measures influential content on Twitter by calculating the followers’ retweets and the recency of those tweets. The higher the number, the more influential the activists are. Based on that feature, the selected Twitter activists have different degrees of social authority ranging between 33 to 86, nodes 0 to 5 have high scores and nodes 6 to 11 have low scores on the social authority scale.

2- Period of the study

a. I covered Twitter activities of each selected activist from March 1st to March 15th of 2017. The significance of this period relies on the fact that the International Women’s Day occurred during this time, i.e. March 8th. I scrutinized every activists’ tweets, retweets, and their corresponding retweets and favorites a week before, during and after the International Women’s Day.

3- General information of each activist

a. I have extracted the activists’ account names and real names if applicable, total number of tweets, followings, and followers, and account age as shown in Table 1 below.

4- Tweets, Retweets and their Corresponding Retweets and Favorites

a. For each activist, I have extracted their tweets and retweets related to women’s rights and all the corresponding retweets and favorites from March 1st to 15th of 2017 by using the software “Twlets”.

5- Network Density

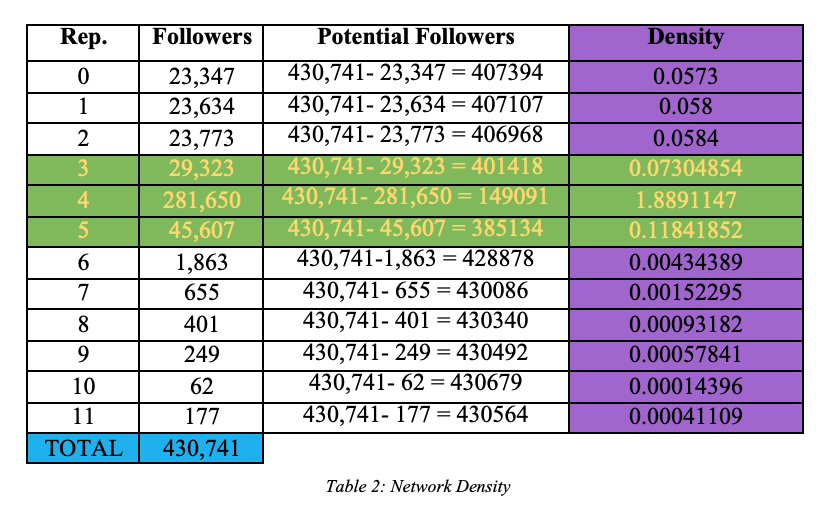

a. To measure network density, I have divided the actual connections (the number of each activist’s followers) by the potential connections (the sum of all activists’ followers subtracted by each activist’s followers). See Table 2 for details.

6- Network Centrality

a. For this study, I measured network centrality by the total number of followers of each activist. Since there is a positive correlation between the centrality and density (the more followers, the denser the network is), I will consider the density scores throughout the study.

7- Circulation of Discourse

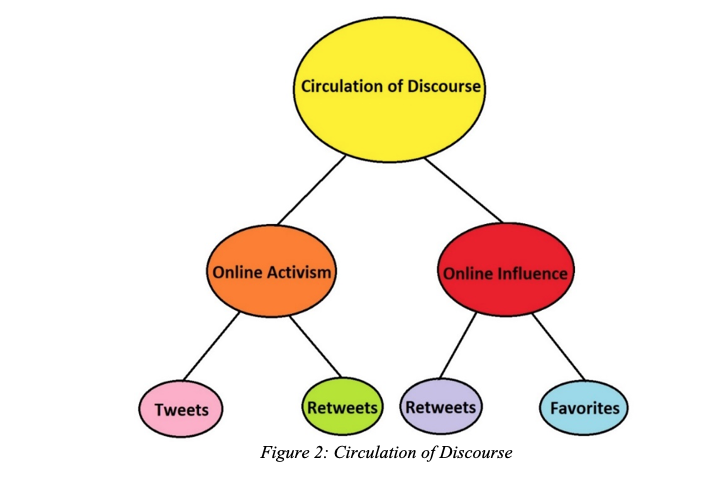

a. Since the rhetorical circulation or circulation of discourse is responsible for creating a public, the circulation of discourse in this study is online activism and online influence, explained as follows:

i. Online activism (I measured online activism by the total number of tweets and retweets of each activist).

ii. Online influence (I measured online influence by the total number of corresponding retweets and favorites). See Figure 2 for visual illustration.

Discussion

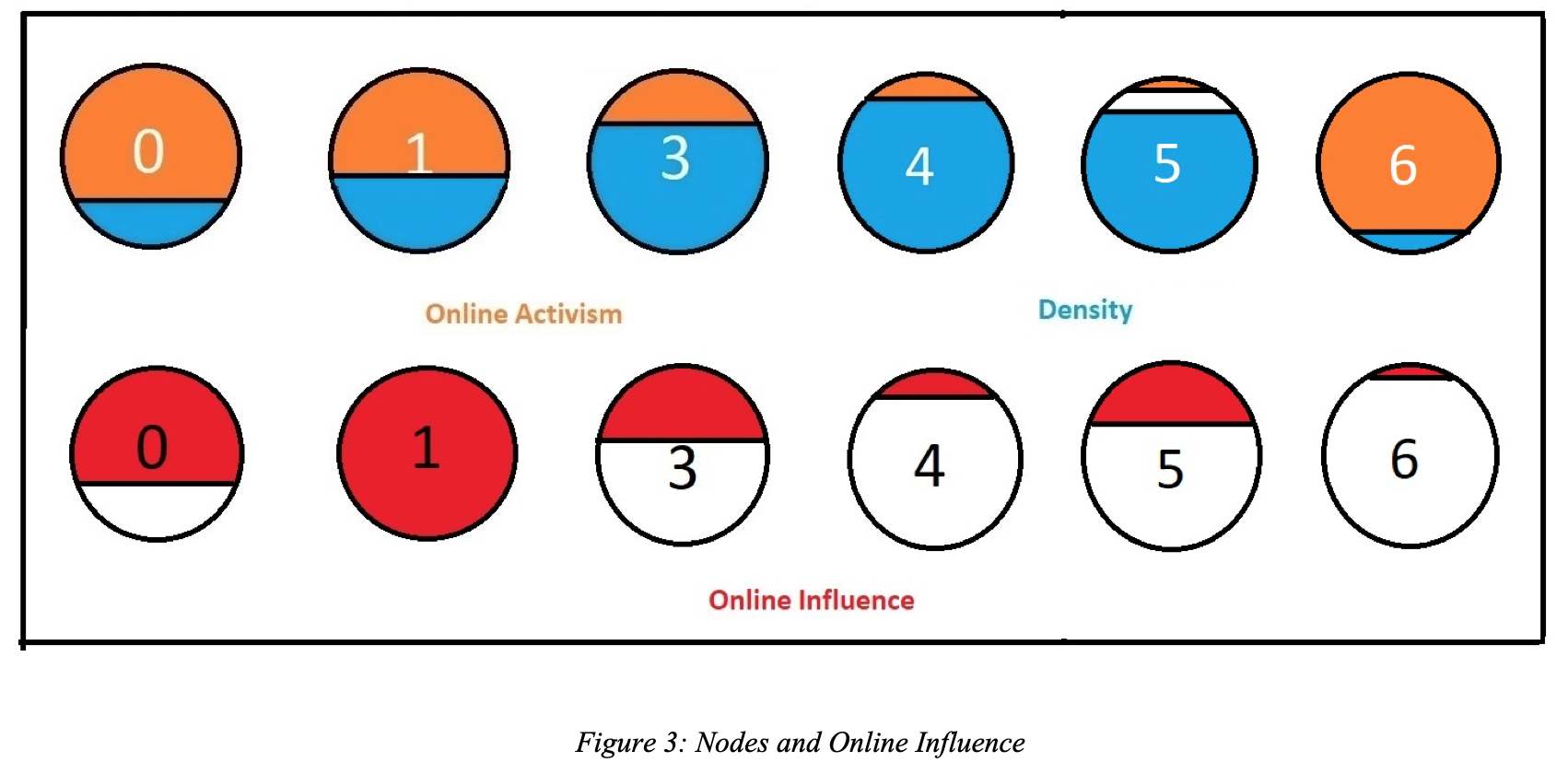

As we can see in Table 3 above, the top three nodes who scored the highest online activism intensity are nodes 0,1, and 6; nodes 3,4, and 5 are the top three in scoring the highest betweenness/centrality scores (number of followers) and accordingly, the highest network density; and the top three nodes who scored the highest online influence are nodes 0,1, and 3. We notice that nodes 4 and 6, the highest network density and the highest online activism intensity among the group, respectively, score very minimal in online influence. However, node 1, the highest online influence among the group, scores lower than nodes 4 and 6 in network density and online activism intensity, respectively. To avoid confusion, Figure 3 below is a visual illustration, although not precise, of the nodes that I have mentioned and their online activism, network density, and online influence relationships among each other.

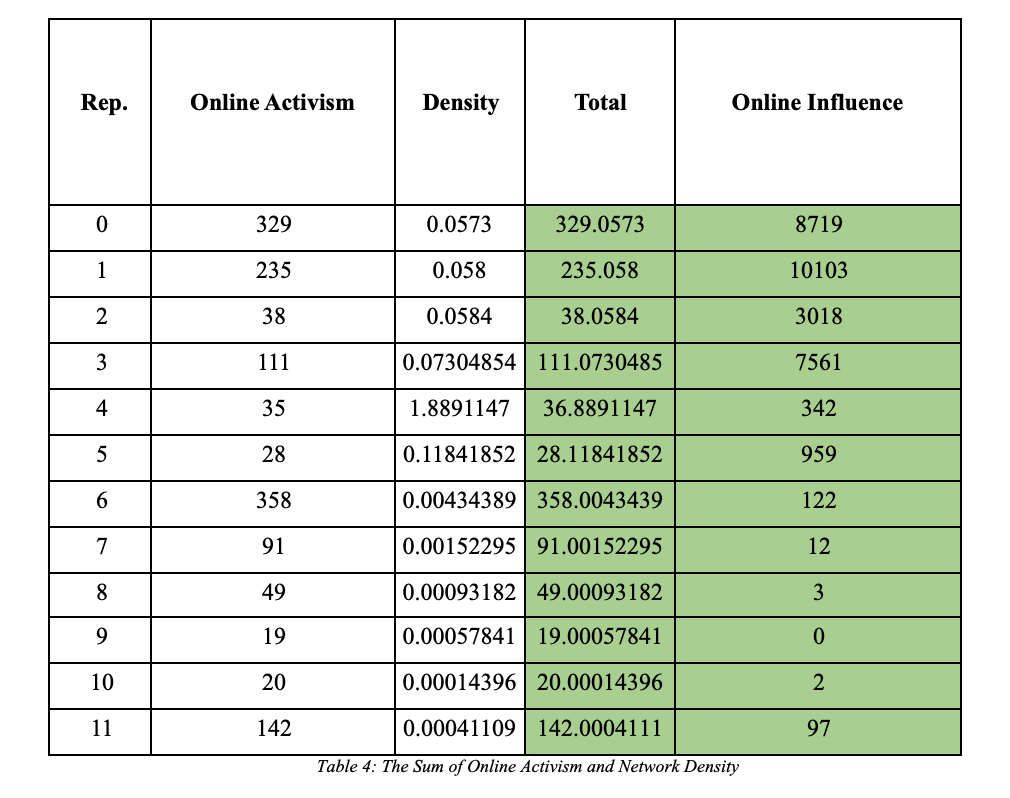

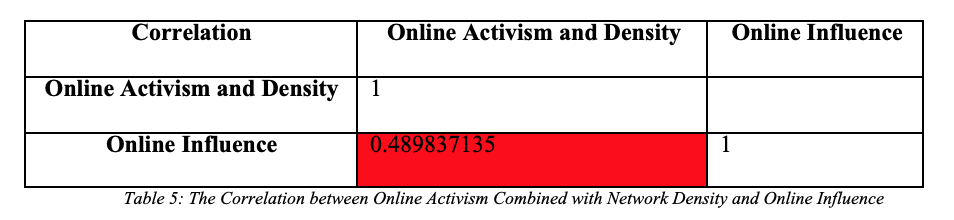

However, how can we determine if the highest online impact was a result of the highest online activism intensity combined with the highest network density or not? Based on the centrality and density theory, the augmented online activism associated with high network centrality and density will yield high online influence. Therefore, I considered a correlation coefficient test between online activism combined with network density and online influence. To conduct the test, I added the online activism total scores to the network density scores. Then, I calculated the correlation between two variables, the sum of the online activism scores and the network density scores with the online influence scores. See Table 4 below for more details.

Based on the result in Table 5 above, the correlation score is 0.4 89837135 which means that there is a positive correlation between the two variables. As a result, the data shows that augmented online activism and high network centrality and density are both essential for better information transmission and greater awareness, hence high online influence. Since high online activism and network centrality and density are key in effecting online influence, and the circulation of discourse (online activism and online influence) is responsible for creating a public and affecting the conditions/ways of achieving social and political purposes, then the magnitude of a public and activism results (online influence) are contingent on network centrality and density.

Finally, the data shows no significant difference between the effect of online activism and network centrality and density on online influence of well-known or pseudonyms activists which supports Michael Warner’s theory that proclaims a public as a relation among strangers through participation alone over time (pp. 55-56).

Conclusion and Recommendations

The significance of this study is to understand the role of social media in supporting women’s rights activism in Saudi Arabia to counter-public, counter-discourse, and connect with other socially excluded women to challenge the discursive boundaries of the public. Women’s rights activists used Twitter as a platform to generate the rhetorical circulation or circulation of discourse (i.e. online activism: tweets and retweets, and online influence: corresponding retweets and favorites) through the help of their followers and network centrality and density. The higher the online activism intensity of the activists are while they have a high number of followers (central and dense networks), the more they effect online influence.

To conclude, we can sum up that this study illustrates a positive correlation between augmented online activism combined with high network centrality and density and high online influence. Network theory, especially network centrality and density are not the only factors that affect rhetorical circulation and consequently, the magnitude of a public, but also, it is of a paramount significance in examining, measuring, and analyzing a public on social media. It is important to understand how we can achieve better awareness and greater transmission within online social networks if social or political redress is intended. This study is designed as a prototype methodology for further research on the effect of network centrality and density on rhetorical circulation on different activism cases on Twitter. Doing so will enable us to understand, affirm, and test the theories/correlations on different data sets that may be belong to different cultural and social contexts.

However, this study is not devoid from limitations or challenges, and subsequently, I will provide some recommendations for future research. Among the limitations that surfaced in my research was the paucity of information pertaining to the activists’ identity, especially the pseudonym activists. This could be due to the culture conservativeness or intimidation by the government since some activists have received warnings or have been penalized for driving and/or participating in the women’s rights movement. For example, node 4 has a very low online activism intensity and online influence. As mentioned before, node 4 was jailed for 73 days in 2014-2015 and this could have affected or limited her online participation during this specific period of study. Furthermore, the accuracy of “social authority” feature which was provided by Followerwonk application is not definite. This feature measures influential content by calculating the followers’ retweets and the recency of those tweets. Those tweets and retweets could be non-women-rights-related. Moreover, scrutinizing 1,900 tweets and retweets to find out which tweets and retweets are women’s rights-related-topics was a bit challenging since it was hard to find an application that analyzes tweets or catches keywords in Arabic. The lack of adequate applications/software was among the reasons that affected my decision in selecting the number of activists.

For future research, I recommend examining a bigger sample of activists’ networks and covering a longer period of time to further test the theories in a more comprehensive way. This sample will be divided into two sections, 1) the nodes that have the highest network centrality density (since the goal is to test the effect of network centrality and density on the rhetorical circulation), and 2) the mutual followers of those nodes.

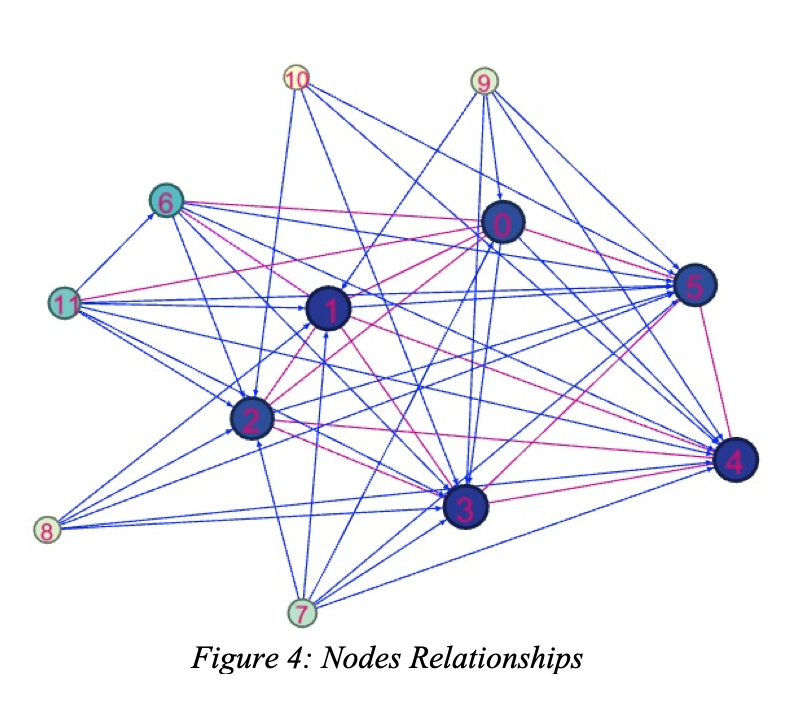

Finally, network theory can provide a variety of ways/approaches, beyond the scope of this study, to study, measure, and analyze networks on social media and to understand their effect on rhetorical circulation and a public. For instance, identifying and analyzing dyadic (directed and nondirected) and clique relationships within networks is another good indicator of network cohesiveness, hence, better information diffusion and online influence (Kadushin, 2012, pp. 29-47). This method could be used to further research in online activism. See Figure 4 below for nodes relationships.

References

Al-Fawzan, S. (2014, November 23). "Expat drivers harass our women." Saudi Gazette. Retrieved from http://saudigazette.com.sa/article/104488/Expat-drivers-harass-our-women.

al-Māniʿ, ʿĀ. M., and āl-Shaykh, Ḥ. M. (2013, February). Al-Sādis min nūfambir: al-marʾa wa qīyādat al-sīyāra, 1990. Beirut: Jadawel.

Al-Saif, M. (2013, February 03). "Gender segregation in higher education." Arab News. Retrieved from http://www.arabnews.com/gender-segregation-higher-education.

"Dozens of Saudi Arabian women drive cars on day of protest against ban." (2013, October 26). The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/26/saudi-arabia-woman-driving-car-ban.

Fahim, K. (2018, November 20). "Jailed Saudi women's rights activists said to face electric shocks, beatings and other abuse." The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/saudi-womens-rights-advocates-reportedly-abused-while-in-prison/2018/11/20/9e77f11c-ebfb-11e8-9236-bb94154151d2_story.html?utm_term=.5e59e10f313c.

Fayyaz, A. (2013, July 15). "Poor public transport hits low income group." Arab News. Retrieved from http://www.arabnews.com/news/458068.

Hubbard, B. (2017, September 26). "Saudi Arabia Agrees to Let Women Drive." The New York Times Retrieved February 01, 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/26/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-women-drive.html.

Human Rights Watch. (2013, October 24). "Saudi Arabia: End driving ban for women." Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/10/24/saudi-arabia-end-driving-ban-women.

Inabinet, B. (2012). "Democratic Circulation: Jacksonian Lithographs in U.S. Public Discourse." Rhetoric and Public Affairs 15(4), 659-666. Michigan State University Press. Retrieved February 8, 2018, from Project MUSE database.

Kadushin, C. (2012). Understanding social networks: Theories, concepts, and findings. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kéchichian, J. A. (2013). Legal and political reforms in Saʻudi arabia. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge. Retrieved from http://www2.lib.ncsu.edu/catalog/record/NCSU2735288.

Khan, F. (2014, November 17). "Street harassment of women on the rise." Arab News. Retrieved from http://www.arabnews.com/saudi-arabia/news/661716.

Knoke, D., and Yang, S. (2008). Social network analysis. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Mackey, R. (2015, February 12). "Saudi women free after 73 days in jail for driving." The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/13/world/middleeast/saudi-women-free-after-73-days-in-jail-for-driving.html.

McDuffee, A. (2014, December 25). "Saudi women drivers sent to terrorism court." The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/12/saudi-women-drivers-sent-to-terrorism-court/384057/.

O'Rourke, S. (2012). "Circulation and Noncirculation of Photographic Texts in the Civil Rights Movement: A Case Study of the Rhetoric of Control." Rhetoric and Public Affairs, 15(4), 685-694. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41940631.

"Private drivers and sexual harassment." (2017, November 10). Saudi Gazette. Retrieved from http://saudigazette.com.sa/article/521528/SAUDI-ARABIA/Private-drivers-and-sexual-harassment.

"Saudi Arabia driving ban on women to be lifted." (2017, September 27). BBC News. Retrieved February 09, 2018, from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-41408195.

"Saudi driver kidnaps a girl' hashtag goes viral in Saudi Arabia." (2018, September 12). Al Bawaba. Retrieved from https://www.albawaba.com/loop/‘saudi-driver-kidnaps-girl’-hashtag-goes-viral-saudi-arabia-1185316.

Saudi government الحكومة السعودية: Lift the ban on women driving رفع الحظر عن قيادة المرأة. Retrieved March 4, 2017, from https://www.change.org/p/saudi-government-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%83%D9%88%D9%85%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B9%D9%88%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A9-lift-the-ban-on-women-driving-%D8%B1%D9%81%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D8%B8%D8%B1-%D8%B9%D9%86-%D9%82%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B1%D8%A3%D8%A9?share_id=HZoizxoMiq&utm_campaign=share_button_action_box&utm_medium=facebook&utm_source=share_petition.

Stanglin, D. (2013, October 10). "Saudi women gear up for driving protest." Oct. 26. USA Today. Retrieved March 03, 2017, from http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2013/10/10/saudi-arabia-women-driving-protest-october/2958833.

"Study shows accidents involving female teachers on the rise." (2015, August 22). Saudi Gazette. Retrieved from http://saudigazette.com.sa/article/139556.

"Traffic accidents occur every minute in KSA." (2015, March 12). Arab News. Retrieved from http://www.arabnews.com/saudi-arabia/news/717596.

Warner, M. (2002). "Publics and Counterpublics." Public Culture 14(1), 49-90. Duke University Press. Retrieved February 8, 2018, from Project MUSE database.

Wyke, T. (2016, May 26). "Saudi man shoots doctor after he delivered wife's baby because he didn't want man to see her naked." The Daily Mail. Retrieved from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3610866/Saudi-father-shoots-doctor-shortly-delivered-wife-s-baby-didn-t-want-man-spouse-naked.html.