I. Queer: There was a boy

a very strange enchanted boy

They say he wandered very far over land and sea

A little shy and wide of eyes

But very wise was he

The greatest thing you’ll ever know

Is to be loved, and be loved in return

—Nature Boy recorded by Nat King Cole, 1948. Lyrics and music by Eden Ahbez

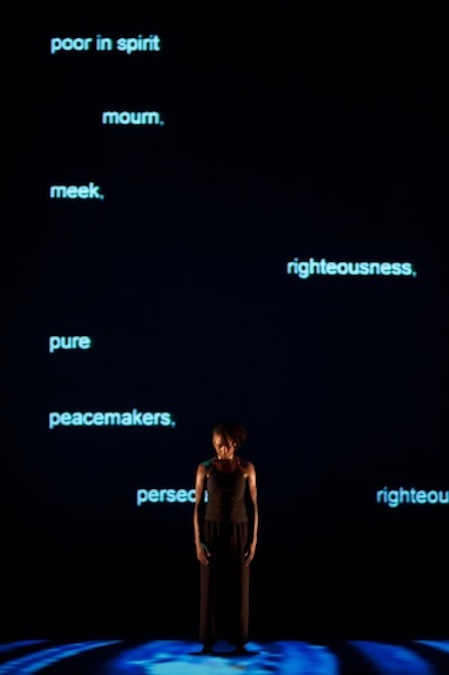

Award winning choreographer and dancer David Rousseve’s newest work is titled Stardust.1 It is a multimedia dance theater piece, exploring a coming of age story through dance, movement, visual images, and text messages projected on to the stage, music by Nat King Cole, and original music/sound design by d. Sabela Grimes. Stardust is a meditation on the search for connection, love, expression of tenderness and desire. It is a story of a young black man at the time of his sexual awakening. We never see him on stage; we only hear from him through text messages projected on to the stage. He is referred to as Junior, Little Man. His inner most thoughts, insights about the world and life are enacted on stage through the dancers’ movements. (He asks: “Peoples in my head??!! They b street niggas or angels???”)

Short texts appear on screen, accompanied by a “ping” (what tweets once sounded like). Text messages convey stories about Junior’s school experiences—of being bullied and being a bully, as well as his conversations with Miss Thelma, his counselor. These messages express his longing to love and be loved. They also share his insights about Van Gogh’s The Starry Night, scenes of tenderness with his grandfather when they listened to Nat King Cole’s music. These texts also tell us what happens when Junior professes his “love jones for Big Man D.”

“I love u Big Man D.

I like 2 give u blowjob.”

Damn he look MAD MAD MAD!!!!! >:-/

Look round like make sure nobody hear me.

Hit me in mouth and knock out front tooths.

I fall ground.

OUCH!!!!!! <:’-(

Photo Credit: Stardust. Performer pictured: Taisha Paggett. Photo by Valerie Oliveiro. Used with Permission.

II. Now: For all we know, we may never meet again

Before you go, make this moment sweet again

We won’t say good night until the last minute

I’ll hold my hand and my heart will be in it

For all we know this may only be a dream

We came and go like a ripple in a stream

So love me tonight, tomorrow is made for some

Tomorrow may never come for all we know.

—“For All We Know.” Recorded by The Nat King Cole Trio in 1949. Lyrics by Sam M. Lewis, music by J. Fred Coots.

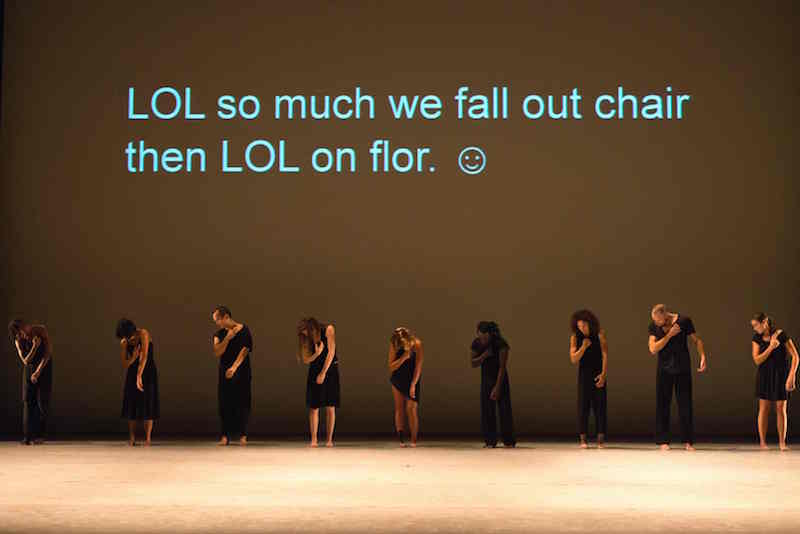

Rousseve describes this project as a coming of age story for the Twitter generation. Projecting now in the form of text messages in vernacular language identified as black or urban/youth English. An iPhone appears on stage, on to which Junior’s Grandfather’s Skypes come in. Grandpa at first is unfamiliar with “skyte,” but he speaks through it, sending encouragement to Junior. It is not until later in the piece that we find out that Grandpa is in fact “skyting” from the afterlife. The piece thus expresses the long time link made between (new) technology, spirituality, other life forms communicating through mechanical invention.

As the piece dares to explore social media in the form of Twitter, texting, and Skype—new-ish forms of human communication and social connectivity—theater itself becomes a focus for me. What is the function or role of theater as technology in this Twitter/Instagram/YouTube generation?

III. Mediated Connectivity: It is only a paper moon

Sailing over a cardboard sea

But it wouldn't be make-believe

If you believe in me

It's a Barnum and Bailey world

Just as phony as it can be

But it wouldn't be make-believe

If you believe in me

—Paper Moon. Recorded by The Nat King Cole trio, 1944. Lyrics by E. Y. Hamburg and Billy Rose (1933)

For those of us who came into theater as a social practice, theater promised the possibility of collective action by providing a shared space and experience. Together in the flesh, next to each other, electric even revolutionary sparks could move us collectively. Break down the fourth wall because it was in the way of spontaneous collective action, leaving the space between performers and the audience without barriers. Yet the building traps us all together, containing (and perhaps simmering) our energy. So while I’m in the theater, watching rehearsals of Stardust in my role as the dramaturg, my thoughts wander away from the stage—text, Instagram, and other forms of social media that bring us the joy of almost instant sharing, and they attempt to remedy the burden of long distance. Their reach is far, wide, and countless. As this multi-media production considers other forms of technology to share human expressions, somehow theater itself as technology disappears, reifying newer technologies—through displays of multi-media—as new techniques to further communicate, express, and interrogate emerging social relations and new social identities. My critical eye and ears are acutely attuned to the disconnections between various forms of technology—how do we know the text projected on to the screen is a text message? Is it a text or a tweet? What experience, sensation does a text message produce and how do we capture that in theater? How do we express that in another medium? What is the now that these new technologies for human communication produces?

Photo Credit: Stardust. Performer pictured: Reality Co. Members.2 Photo by Valerie Oliveiro. Used with Permission.

IV. And now the purple dusk of twilight time

Steals across the meadow of my heart.

High up in the stars, the little stars climb,

Always reminding me that we’re apart.

Love is now the stardust of yesterday

The music of years goneby.

—Stardust. Recorded bysung Nat King Cole, 1957. Lyrics by Hoagy Carmichael and Mitchell Parish

Postmodern dance? Multi-media performance? Coming of age for the twitter generation? Set to NAT KING COLE’s music? Nearly three years ago, when Rousseve first invited me to sit through an initial showing of this work in progress, I shared with him that what I find risky about this postmodern multi-media piece is his use of Nat King Cole music—music that is so recognizable, sentimental, lyrical, expository, and narrative. He choreographed what we would call “dancey dances,” not always fighting with the sound, but rather moving rhythmically with the music. Dance that didn’t comment on itself and its constructedness. Dances that allowed the audience to stay with it, not a meta-commentary about the process of experiencing live performance, of the disappeared labor in dance, or erasure of power relations between the bodies on stage. Stardust also has tender duets, forceful trios, and frenetic solos. Crotch grabs and chest pumps represent the concept of everyday movement of urban youth. A postmodern multi-media production about the precarity of black youth life that is cathartic. The opening is seven minutes of meditative, prayer-like movements, set to night sounds (cricket chirps, faint dog barkings).

My favorite parts of Stardust are the seemingly random movements, such as the screaming match between two performers. The performers stand across the stage, facing the audience. One performer (A) calls out another (B) to meet her down stage center. They face each other. The one who called out the other performer (A) suddenly screams at the top of her lungs to performer B’s face. Performer B plays along and it’s a screaming fest. Performer B begins to feel good, gets into the spirit of the contest. She gears up for another round, only to turn to an empty space because Performer A left—the game got old to Performer A just when Performer B caught on. Who can out scream the other—without gadgets other than our voice? It’s this kind of simplicity and poignancy that reminds me of what remains possible and special in theater. Rousseve’s works have always been full of these—a simple children’s game transformed, and made to dramatize the bitter sweetness of difference, of becoming, of the human condition.

Notes

1STARDUST. World Premiere January 2014. Co-Commissioned by Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center (University of Maryland), Krannert Center for the Performing Arts (University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign), Peak Performances (Montclair State University). Artists collaborators include Cari Ann Shim Sham (Video), d. Sabela Grimes (Music and Sound Design), Chris Kuhl (Lighting), Lucy Burns (Dramaturgy), Lea Pahl (Costume).

2Reality Dance Company members: Taisha Paggett, Jasmine Jawato, Nguyen Nguyen, Emilie Beattie, Charice Skye Aguirre, Michel Kouakou, Nahara Kalev, Kevin Williamson, Leanne IaCovetta, and Kevin Le.